Restoring prairie and sinking carbon in Colorado

Sinking carbon on solar farms: a new kind of PV + storage

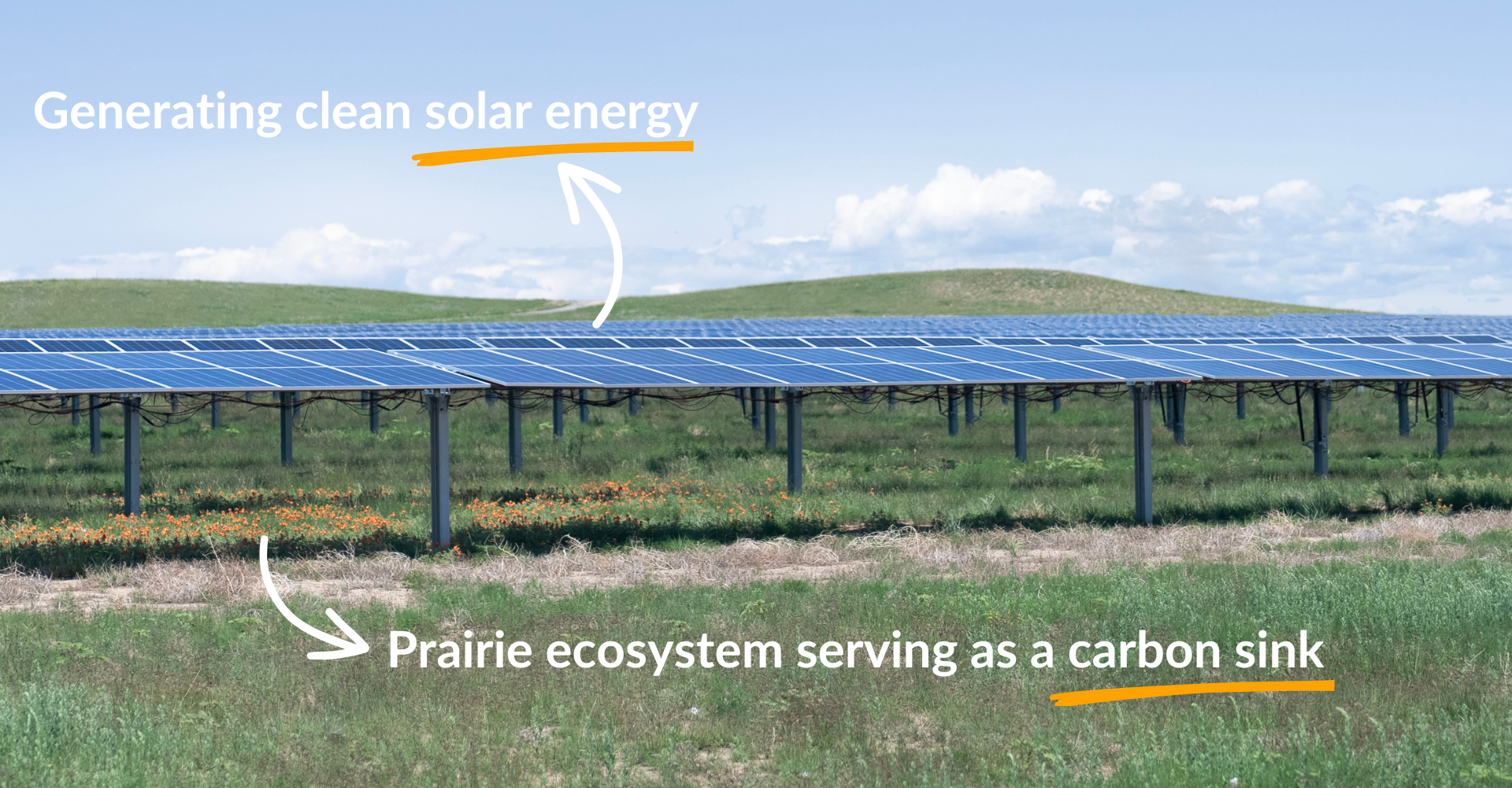

At two projects in Pueblo, Colorado, the Lightsource bp team is taking steps beyond clean energy generation with an innovative Land Management and Biodiversity Plan. In addition to providing emissions-free energy, the sites will serve as a biodiversity haven and carbon “sink,” pumping CO2 from the air into the soil and vegetation on-site.

As the final step of this program, we introduced rotational sheep grazing to the projects in 2024. Through this approach, nearly 4,000 sheep will help maintain the native vegetation and further enrich the soil under and around the solar panels.

Enhancing biodiversity with short-grass prairie conservation

The utility-scale solar farms are in the southwestern tablelands, a semi-arid ecoregion at the western edge of the central great plains. The projects lie within a short grass prairie ecosystem, once home to free-ranging bison and grizzly bears, and today dominated by grazing livestock.

As part of Lightsource bp’s commitment to increase net biodiversity on its project sites, the 300 MW and 293MW solar farms have been designed to serve a dual purpose: delivering renewable energy to lower carbon emissions from electricity generation while sharing the land with conserved shortgrass prairie habitat. In all, 3,051 acres of shortgrass prairie will grow on and surrounding the Bighorn and Sun Mountain Solar sites.

Before construction began, Lightsource bp and partners designed a site-specific seed mix, suited to the local climate, ecosystem and soil. The mix contains staple short grasses like western wheatgrass, buffalograss and little bluestem, as well as a low concentration of purple prairie clover to provide nectar for pollinating insects.

During construction, the teams minimized disturbance of existing ground layer as much as possible. They reestablished high-quality habitat on disturbed areas and enhanced existing vegetation with the native seed mix. These species will quickly stabilize the soil and minimize erosion as their root systems develop.

These management practices help control undesirable weeds, allowing the native grasses to establish and proliferate. Many of Colorado’s noxious weed species spread rapidly, increasing wildfire potential and injuring people and animals with spiky seeds.

This conserved prairie habitat will additionally provide a safe home for invertebrates like native bees, small mammals and prairie songbirds.

Re-introducing rotational grazing on the land

The native plants of Colorado’s short-grass prairie region evolved when herds of wild grazing animals like buffalo roamed across the American plains. These herds played a crucial role in the ecosystem. As they moved around the landscape, they’d spread rich manure, kept biodiversity in balance and physically altered the soil with their hooves.

In 2024, we partnered with a Colorado ranch family to re-introducing those benefits to the ecosystem, with nearly 4,000 sheep across the two sites. Well-managed rotational livestock grazing will encourage the native plants to grow robustly. The ranchers will strategically move the flock from one area of each site to the next from spring to fall, the sheep trampling good seeds into the soil and selectively eating away invasive weeds in each “paddock”.

Enhancing decarbonization with carbon sequestration

During photosynthesis, plants convert carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into sugars and carbohydrates, stored within the plant matter. In a prairie ecosystem, the bulk of carbon-storing plant matter lives underground in the deep roots of grasses and other species. When these root systems die, they decompose and become carbon-rich soil, which can remain underground for hundreds to thousands of years. In this way, prairie habitat acts as a “carbon sink,” pulling C02 underground to reduce its concentration in the atmosphere.

The addition of sheep grazing will enrich the soil even more—managed grazing has been proven to improve soil quality and carbon sequestration at solar sites. This is because the sheep leave behind plentiful “droppings” across the land, which contain lots of organic matter and water. As they trample their waste into the ground, the sheep add carbon, other nutrients and hydration into the soil.

The Bighorn and Sun Mountain projects will remain undisturbed for decades, allowing for many generations of shortgrass prairie plants to live and die on-site, and many generations of sheep to spread plenty of rich manure. Research data indicates that over the first 25 years of the projects’ 40-year lifespan, the on-site prairie habitat will remove and store the equivalent of 36,000 tons of CO2.

Soil samples were collected at the start of the project to establish baseline soil carbon. Future sampling will determine the total amount of soil carbon increase over time, due to reestablishment of shortgrass prairie habitat. We predict that carbon storage in the site’s soil will increase about 17% over the project’s life.

In addition to mitigating climate change, the addition of extra carbon will further fertilize deep layers of soil to provide a strong foundation for the entire ecosystem of plants, animals and microbes.

Discover Multiuse Solar

Discover Multiuse Solar

This project is one example of our commitment to co-locating responsibly sited solar projects with other land uses in the United States—an approach dubbed “dual-use solar.” Lightsource bp often goes a step further, building multiuse solar projects where clean energy generation shares land with multiple initiatives including agriculture, conservation, and research.

More Responsible Solar stories

03 Apr, 2025

Community hospital check presentation, job fair kick off Lightsource bp Jones City energy center in Jones County, Texas

Community partnerships in Texas

19 Feb, 2025

Video: Honeysuckle Solar drives American manufacturing close to home

Indiana project includes locally manufactured parts